Amidst the more modern themes, my last blog seems to have created a fair bit of interest in Alfred Cotgreave; indeed he probably shot up the Google search list for the first time since his death in 1911. But to answer last month’s question about the last UK library to abandon ‘closed access’: in Kilkenny, Ireland so not actually UK, it seems that the City or Carnegie Library was using a Cotgreave Indicator until the early 1940s, and Stornoway Library in the Isle of Lewis was reported to still be operating with an indicator and closed access in 1948!

But there was more to Alfred than the indicator he invented so, if you keep reading to the end, I’ll give you a further insight into the working life of a librarian in the late 19th century.

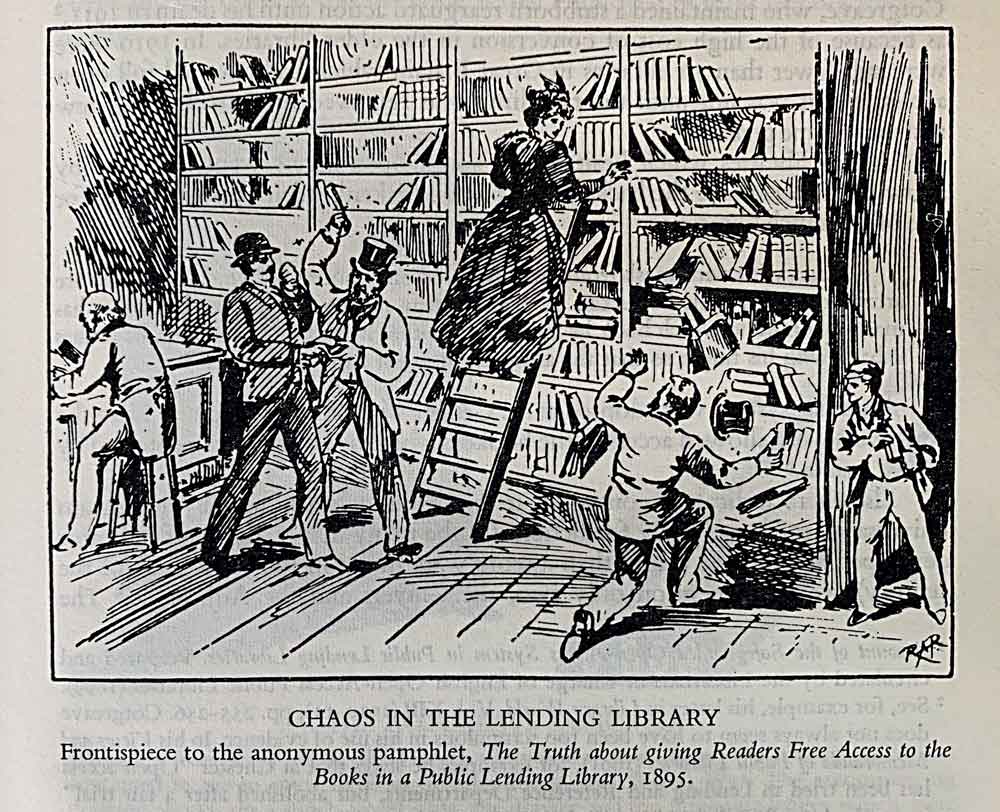

This year most public libraries returned once again to closed access as a partial work-around in a world dominated by the Coronavirus. This was of course a step backward, but library staff could be forgiven for deriving some small pleasure from not having to constantly tidy the library and its shelves. Certainly, their counterparts a hundred or so years ago believed that letting the public loose amongst the books would create chaos:

As we near the close of 2020 (no pun intended there), a further wave of COVID-19 has unfortunately overtaken the best efforts of service managers to reopen libraries with anything like the level of service on offer at the beginning of the year. Last month I recommended the research report by Libraries Connected, which demonstrates the creativity with which many library services and their staff responded to the pandemic, increasing digital and other forms of online access during lockdown and then starting to reopen physical access to libraries and their stock. We’re now seeing reopening plans put on hold, and in some areas library buildings forced to close again, indeed in Wales libraries were instructed to close during the recent ‘circuit-breaker’ and at the time of writing I’m unsure what is happening there after 9 November. While this will frustrate library staff I can’t help wondering if it’s a little too convenient for policymakers looking for longer-term cutbacks. In any case, notwithstanding the successes highlighted in the LC report, there was already a wide variation in the library offer users were experiencing across the country during the summer, often in neighbouring local authorities.

The joint letter the Minister at DCMS and the LGA Chair sent to Council Leaders and Chief Executives in England in July was timely (there’s a copy on page 51 of the LC report), and it helpfully linked to updated guidance on Libraries as a Statutory Service. (Not forgetting of course that oversight of public libraries in Scotland, Wales and N. Ireland sits with the devolved legislatures). But there remain key questions for when Covid-19 is finally brought under control: At what point will local authorities be required to return their public library service to something more closely resembling their offer before this crisis? What will ‘Comprehensive and Efficient’ be expected to look like then? And how vigorously will this be monitored and enforced?

Nevertheless, at Activist we’re looking at how all that’s been happening recently could be turned around, offering the opportunity to re-focus the vision, purpose, and indeed the delivery model of library services. At the beginning of 2020 pretty much everyone had in place a forward plan for the next one, three, five years, but how relevant will that still be when in 2021, hopefully, we all start to come out of the other side of this? I’ll return to this theme in my next blog.

Staying with the ‘upbeat’, COVID is now drawing attention to the benefits of advances in technology for libraries. How about a Contactless app that you can download to your mobile phone and then use to check-in/check-out library items, access digital content, or receive service information updates? I spotted this a while ago and thought “What a good idea!”, but now that COVID has obsessed us all with what we touch and with how we interact with customers and colleagues, the potential seems huge. This article by Liz McGettigan of SOLUS, who market the app (no, sadly it wasn’t my invention!), explains how this works in more detail.

I also saw recently that in the U.S. some libraries are purchasing an ‘Ultraviolet Ray Book Sterilizer’ to get around the need to quarantine returned books and other materials. Have any UK library services gone down this route? I’m more doubtful about this domestic version on the market, which you could place in your hallway to ‘zap’ your keys, phone and other items when you return home. That’s assuming you don’t mind visitors thinking you have a microwave just inside your front door – it will not be on my Christmas wish list!

But returning to Mr Cotgreave: so, you think it’s tough running a public library service today? After Alfred had invented in 1877 the indicator which, as one of the earliest attempts at library ‘automation’, made his name in the professional world of his day, he went on to apply to be the first librarian of the newly opened Richmond Library, Surrey. Cotgreave was selected from 250 applicants for the post, which was advertised at the princely salary of £400 per annum and with unfurnished accommodation above the library. The library opened from 9am-10pm Monday to Saturday and Cotgreave appears to have initially been expected to run it on his own, as after three months it was so busy that he was pleading with the committee for an assistant and was given permission “to appoint a boy at 4 shillings a week”! When I went to work there (sometime later!) the librarian’s rooms, accessed by a winding staircase, were used as offices and a staffroom, though apart from that seemed largely unchanged!

Geoff Allen is a senior associate consultant with Activist Group. The views expressed in this blog are his own and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Activist.