… at your local library

In 2020, notwithstanding the ongoing digital divide, 96% of households in the UK had some level of access to the internet, but this brings with it a danger that has never been more stark than during the frenetic events of the past year. The problem is that anyone and everyone can and does disseminate information on the World Wide Web, if by no other means then via social media, with very little control of its veracity, quality, or currency. “Karen on the internet” has become an urban joke (though not one you’d risk using in the presence of my niece of that name!) but the danger at the heart of this is far from amusing.

So, what has this to do with libraries and librarians? For centuries there has been (at least in free democratic societies) a largely unrestricted plethora of information, though the need to print and publish on paper imposed some constraint. The problem has always been that the average person did not know how to find and distinguish between reliable sources and unfounded opinions or propaganda.

Over recent years new technologies have had an explosive impact on the spread of information. I can still recall the excitement in the reference library caused by the arrival of Ceefax, the world’s first teletext information service, but how basic that now seems … and if you’re below a certain age you’ll probably need to Google ‘ceefax’ to find out what it was! The librarians of Miss Crimp’s day (January Blog) and earlier would have relished the opportunity to use the internet to disseminate and retrieve information, but they certainly would have been very familiar with the skills and techniques needed to distinguish reliable sources from fake news. Once upon a time this meant knowing which books to buy or recommend and which to avoid, and what sources to hold on the reference library shelves, but precisely those same skills can now be applied to the internet.

I suggest that UK libraries should be focusing on this theme at a national and local level. Australia’s national library bodies are calling for “the federal government to adopt a strategy for combating misinformation and disinformation among individuals of all ages”. Professional librarians (and hopefully these days other library staff) are taught skills to evaluate sources and to differentiate the reliable from the dubious or downright fake. Isn’t there now a key role for library services to identify, package and recommend reliable sources, not least via library websites but also of course through library service points when they fully reopen? Some of this is already happening, but with not enough focus within many library services: how many have any reference to this in their service vision or strategy?

At one time public librarians were required to exercise some control over access to ‘undesirable’ material by what amounted to censorship. Books considered unsuitable for general circulation, even though they might have passed legal scrutiny, were often kept ‘behind the counter` or in the book stack and only brought out on request. The blacking out of the racing news in newspapers – an early morning task almost certainly assigned to Mr Cotgreave’s boy assistant in the late C19 – was a practice that only completely ended in the 1960s. But at the same time their narrow world view often precluded the questioning of patriarchal, colonialist and racist narratives, which thankfully are now being challenged, both by conventional researchers and in part by web-based activism.

The Australian cartoonist First Dog on the Moon picks up this theme in the 5 February International Edition of the Guardian, posing the question, “How did we find things out before Google? Remember going to the library!?” and answers with a series of cartoons. I particularly liked this one, “Remember encyclopaedias? They were expensive and racist and immediately out of date but at least they didn’t illegally listen to your conversations and then send you targeted advertising”.

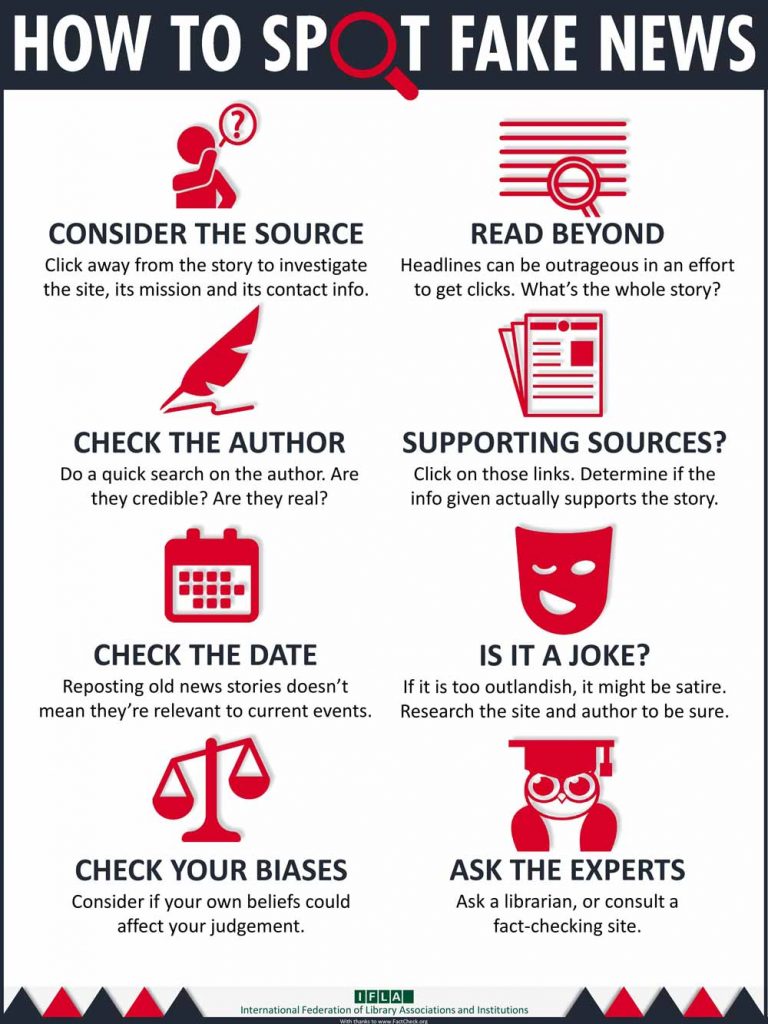

The real answer to today’s overload of information is not, however, censorship. But when it comes to the wider local authority I suspect the role of library staff as information ‘navigators’ is scarcely comprehended, let alone valued. ‘Navigator’ is a key skill, never more vital than in 2021, which needs to be developed and recognised as we move forward. As this excellent poster from IFLA says, Ask the Experts!

Geoff Allen is a senior associate consultant with Activist Group. The views expressed in this blog are his own and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Activist.