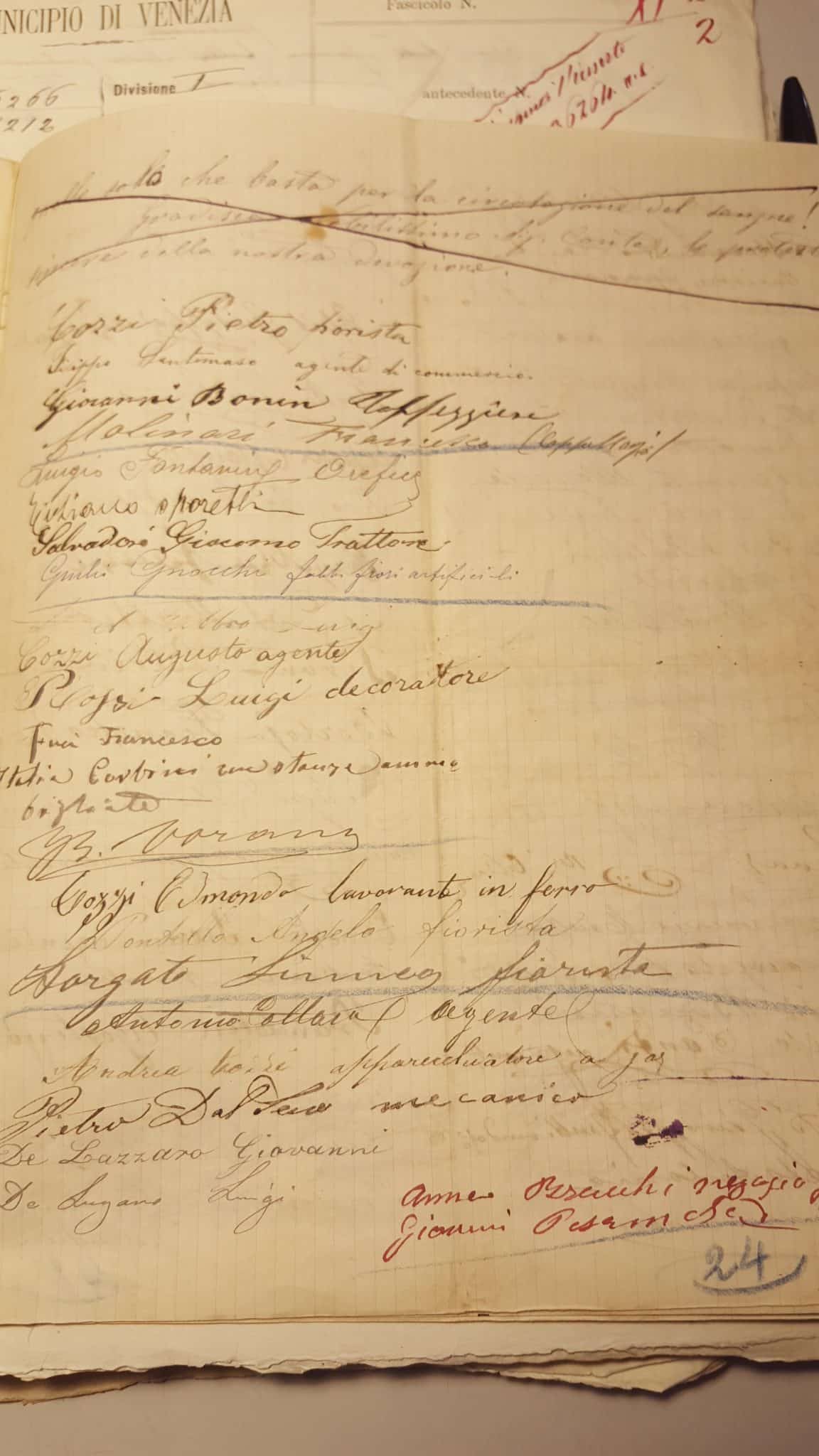

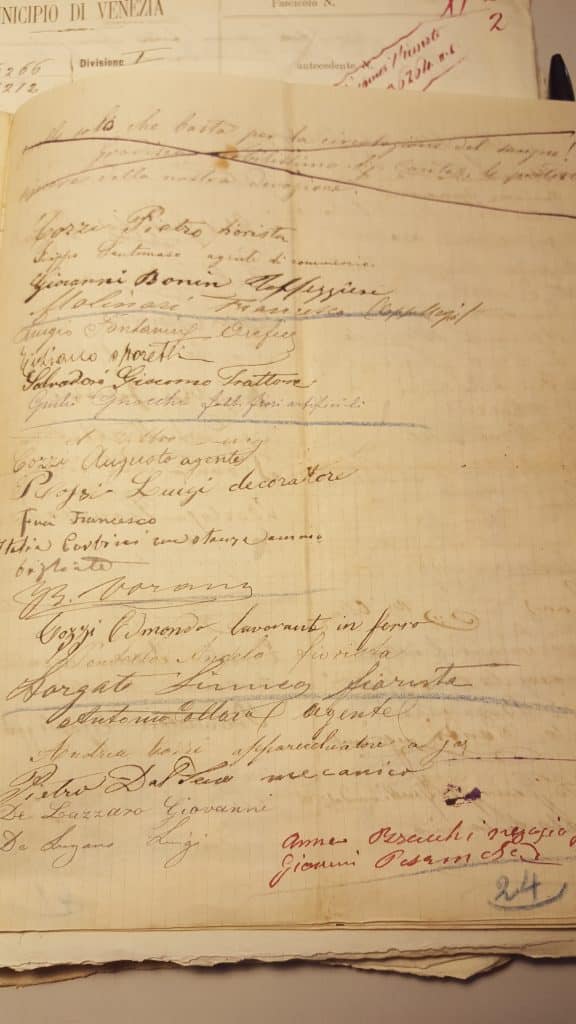

‘Please reopen our theatre!’ Singers and orchestral players obviously, but also florists, tailors, wigmakers, metalworkers, hoteliers, restaurateurs, accountants, gasfitters, mechanics, all desperately pleading for work, with theatres closed in the midst of economic crisis and a public health emergency. Not a social media campaign led by Andrew Lloyd Webber against DCMS during the COVID pandemic, but a petition submitted by indigent Venetians to the city’s mayor over a century ago. Venice’s economy was severely depressed for much of late nineteenth century, and the Fenice opera house struggled to finance regular seasons, leaving all those dependent on its operation short of employment and trade.

The development of the Lido beach resort heralded the modern incarnation of Venice’s tourism model, with the construction of opulent art nouveau hotels like the Excelsior. Nicolò Spada, the Excelsior’s owner, had a vision to turn the Lido into the Italian Bayreuth, modelling a new opera house in the style of Wagner’s festival in Bavaria, and promoting Italian opera to the burgeoning tourist elite visiting Venice. Construction was due to commence in September 1911, when disaster struck in the form of the cholera outbreak that summer, which emptied the city (inspiring Thomas Mann’s novella Death in Venice). Sadly the project for the new opera house was shelved, never to be revived, although the 1912 season at the Lido was reportedly one of the most spectacular.

Wind forward to the COVID pandemic and we can draw some striking parallels. Are we in our own version of 1912? Venice was at the forefront of those tourist meccas reckoning with the pros and cons of the sudden disappearance of mass tourism during the pandemic, though whether it can achieve a more sustainable future looks moot.

Meanwhile in the UK, even among die-hard classical music fans (myself included) few may mourn the collapse of the proposed New Centre for Music at the Barbican in London in 2021. The pandemic proved the last nail in its coffin, compounding the lack of political will to favour the capital with such largesse in a time of ‘levelling-up’. But another year on it feels like superficially the arts and culture are enjoying some semblance of normality now despite the resurgence of rates of COVID.

Yet what of the more fundamental challenges thrown up during the pandemic?

Our Belle Époque Venetian petitioners would certainly recognise the existential crisis which freelancers have faced under COVID. Their plight has been a significant theme in debate in many countries about the survival and recovery of the cultural sector. The UK’s relatively generous support for institutional survival through furlough and the Cultural Recovery Fund threw into contrast the numbers of freelancers left adrift by government schemes, who either temporarily had to take on alternative employment, or who have switched careers permanently. As one of the world’s leading theatre designers described it to me:

“No one had a duty of care towards freelancers in the industry – the silence was deafening”.

This highlighted not only the relative financial insecurity of the vast majority of workers who are the creative lifeblood of arts organisations, but the lack of agency many artists feel outside institutions who depend on their talent but whose voices are not always heard in decision-making.

Arts Council England has long weathered similar complaints from artists who have felt it is just as remote from the needs of practitioners. To its credit, ACE has already taken steps to address some of the inequalities which have been laid bare by the pandemic, commissioning a consortium of freelance representatives to lead a conversation on Freelance Futures, which will inform further changes to its Delivery Plan, including funding available for individuals and guidance for future rounds of its National Portfolio. It would be inspiring to think that this work could drive some fundamental change in the structure of the sector. Attending one of the Freelance Futures events in May along with around 200 others, the consensus was that good intentions had yet to match actions, and that solutions to many problems were yet to be identified. Participants raised a host of issues capable of undermining good intentions – the hollowing out of the stage craft workforce, when many have left performing arts for better terms and conditions in TV and Film; how the cost-of-living crisis is impacting freelancers more than salaried staff when ACE-funded organisations have been told to apply for no increase in funding; and continuing fears among freelancers about voicing concerns when dependent on institutions for work.

It is encouraging that ACE is stimulating and funding this type of conversation, but it is also incumbent on all those organisations – public bodies, charities and commercial enterprises – to reflect as we lurch back hungrily to some semblance of normal cultural activity, whether conditions for those professionals who lack job security, are consistent with the values which we espouse as a sector seeking to support creativity and wellbeing across society.

Dr Andrew Holden is an Associate Director at Activist Group, and a Visiting Researcher in the School of Arts, Oxford Brookes University. Recent publications include ‘A slice of operatic life in London’s East End’, Journal of Modern Italian Studies 26/1 (2021) ‘Italian Musical Migration to London’; ‘From Heaven and Hell to the Grail Hall via Sant’Andrea della Valle: religious identity and the internationalisation of operatic styles in Liberal Italy’ in Körner and Kühls (eds.), Italian Opera in Global and Transnational Perspective: Reimagining Italianità in the Long Nineteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022). He is currently working on a co-edited volume about censorship in the contemporary opera industry.

Andrew Holden is an Associate Director with Activist Group. The views expressed in this blog are his own and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Activist.